Search Results

876 items found for ""

- Happy Birthday, Charlie!

Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle Turns Twenty. If you were a young girl growing up during the early aughts, you knew about and loved, the Drew Barrymore-produced Charlie’s Angels reboot. If you were a middle-aged man going to the movies in late 2000, you were going to check out what this new Charlie’s Angels was all about. If you were a preteen boy watching Charlie’s Angels, you were probably doing so to…well, you get the point. Needless to say, the 2000 McG film, Charlie’s Angels, was a phenomenon. Spearheaded by Barrymore herself, the first film in the Charlie’s Angels series captured the Girl Power energy of the ’90s and married it with the burgeoning, new punk rock scene to great success. Grossing $264.1 million worldwide, against their $93 million budget, Charlie’s Angels was a hit both critically and at the box office. So, it was no surprise when it garnered a sequel three years later, 2003’s Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle. In the 20 years since Full Throttle’s release, however, there have only been two more attempts to keep Charlie’s party going. What was it about the Barrymore films that landed while the others have fallen flat? Let’s solve the case. One of the key determining factors of the success found in 2000’s Charlie’s Angels is that it was conceived by Flower Films, Drew Barrymore’s production company founded by Barrymore and her best friend, Nancy Juvonen (maybe most widely known for being Jimmy Fallon’s wife). The two women pitched the film to Sony Studios by putting together a montage of their favorite action scenes, arguing that their vision would showcase everything they loved in the genre, while also paying tribute to the spirit of the original Charlie’s Angels television show. After selling Sony on their pitch, Sony even allowed them to pick their director. Barrymore picked Joseph McGinty Nichol (known professionally as McG) because she admired his previous work in music videos. With his flair for directing action to music, Charlie’s Angels can sometimes feel more music video than film, but the joining of the two is what really makes the campiness of these two films sing. The beauty of Charlie’s Angels and its sequel is that at their very core, these films don’t take themselves too seriously. In the first of the film franchise, Charlie’s Angels, Natalie, Alex, and Dylan (Cameron Diaz, Lucy Liu, and Barrymore, respectively) take down a young Sam Rockwell’s Eric Knox: the founder of a tech company hellbent on harnessing satellite voice recognition software to find and kill the titular Charles Townsend, who Knox wrongly assumes to be the one who killed his father. The cast is loaded with other great actors (Tim Curry, Matt LeBlanc, Crispin Glover, Kelly Lynch, and Melissa McCarthy) and the Angels are accompanied by this iteration of Bosley in Bill Murray. John Forsyth even reprises his role of Charlie, building the in-world connection that these films are, in fact, connected to the original series. Throughout the film, the Angels go through various reconnaissance missions in order to ascertain and obtain intel, all the while wearing their now iconic series of deep cover costumes, ranging from Oktoberfest yodeling garb to racetrack-ready speed suits. In sum, the film is a total blast. Sadly, in recent years, there have been multiple stories that have come out against Charlie’s Angels' production, and these stories and criticisms can’t be outright ignored. Firstly, in casting news, both Thandiwe Newton and Nia Long have come forward about their possible casting in the film. Long has said that in her audition (for the role of Alex Munday, eventually won by Liu), she was told that she appeared too old in comparison to Barrymore and Diaz. Newton, on the other hand, was closer to taking the role but ultimately turned it down because she didn’t want to be overtly sexualized, especially in the intended objectification of being a biracial woman. Even though Newton brought her issues up with the filmmakers and chose not to be in the film, objectification is still undoubtedly present in the film. At one point, Natalie and Dylan assist Alex in an upscale massage parlor heist all dressed as geishas, and in another scene, the three women seduce a security guard while wearing bindis and Barrymore’s Dylan is (ack!) in undeniable brownface. The last of Charlie’s Angels' debacles came down to Bill Murray’s relationships with both Liu and McG. Murray has seen a number of people come forward in recent years stating that he is difficult to work with: childish at best, verbally and physically abusive at worst. Liu has recounted that he emotionally abused her on set, questioning her acting skills and hurling insults at her. (Liu has stated that they have since reconciled and she holds nothing against him. But she still takes issue with how the media handled the incident by painting Liu - the lesser known of the two, and the woman - as being the difficult person in the situation.) Additionally, Murray and McG also did not get along. These conflicts led to Murray not being asked back for Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle. Murray’s absence, alongside the departure from cultural appropriation, makes for a sequel more happily devoid of controversy. What Charlie’s Angels pulls off in its meager balls-to-the-wall 98-minute running time, Full Throttle doubles down on (with an equally bangin’ soundtrack). Coming in at only 106 minutes, CA: FT packs even more action, more outfits, and more twists than its predecessor. In this story, Natalie, Alex, and Dylan are accompanied by a new Bosley (Jimmy Bosley) played exuberantly by Bernie Mac, Bosley’s adopted brother. The retcon is delivered by explaining that Murray’s John Bosley (who also happens to be the original Bosley from the show) had been adopted into Mac’s family (surname, Bosley) at an earlier age (rewriting Bosley’s storyline to mean he had always been adopted into a black family). While this can come across as a means to better diversify the cast (especially in light of Long’s and Newton’s departure in the initial casting process), I still find this new information extremely enjoyable and heartening. Mac’s presence as Bosley in the sequel breathes new life into an already buoyant franchise, and CA: FT is better off for it. There are a lot of great additions to the sequel that completely change up the film’s dynamics (Demi Moore, Justin Theroux, John Cleese, Shia LaBeouf), but, outside of the Angels, it’s always been Mac that has me coming back time and time again. Outside of a “new” Boz, Full Throttle offers a storyline that the witness protection program’s list of witnesses (within a database housed inside two wearable rings that must be together to be accessed) has been stolen and is going to be sold off to the highest crime family bidder. At the climax of the first act, in a surprise twist, we find out that Barrymore’s Dylan is actually one of the witnesses in the program (real name: Helen Zaas) and the leader of the Irish mob (her ex-boyfriend, Seamus, who she put away) is coming for her. Justin Theroux has the time of his life as Seamus, and out of all the villains in these two films, he brings a campy level of fear that is actually believable. In the villain arena, we also see the return of Crispin Glover’s “Thin Man” from the first film, who actually ends up being Team Angel in all his weird, hair-loving glory. And lastly, Demi Moore plays the big bad as a former Angel (Madison Lee) who had gone rogue in the past and is going rogue again as the mastermind behind the sale of the two rings. It has been argued that Full Throttle lacks a coherently sound plot, but at its core, it’s a story about personal integrity, chosen family, and overcoming your past. The parallel plot within Full Throttle is that Dylan fears that with Natalie and Alex’s relationship success (Natalie with Luke Wilson’s Pete and Alex with Matt LeBlanc’s Jason), they may soon choose to leave the agency, and her, behind to move forward with their lives. There’s a delightful flashforward where Dylan imagines that in Natalie’s departure, she and Alex are joined by the recording artist Eve as the third Angel, and then even further in the future, a much older Dylan sits alongside the Olsen twins as the Angel trio. Dylan’s abandonment issues are kicked into high gear as rumors circle on whether or not Pete is going to pop the question to Natalie, and Madison’s presence as a former Angel only adds to the reality that Angels don’t stick around forever. By the end of the film, Natalie and Alex have reassured Dylan they’re not going anywhere, and Dylan learns to share in their happiness instead of seeing it as an ill omen of her eventual loneliness. Should these Angels probably go to therapy to work through their individual issues? Sure. But does it seem like the Angels end this film in the security of their personal and professional relationships? Heck yeah. In the years since 2003’s Full Throttle, there have been two additions to the Charlie’s Angels oeuvre: a television series on ABC that aired in 2011 and was canceled after one season, and Elizabeth Banks’ 2019 film. As someone who only tangentially knew of the ABC series, I can’t personally speak to its demise, but it has been written that the show leaned too heavily into the dramatic notes of the series and lost almost all of the camp entirely. It, frankly, took itself too seriously. As someone who truly grew up with the two Barrymore films, I just don’t need my Charlie’s Angels to be serious, so I can’t imagine myself ever turning to this reboot of a series. The same could be said for Banks’ 2019 film. Starring Kristen Stewart, Ella Balinska, and Naomi Scott as the Angels, 2019’s Charlie’s Angels takes place in a world where the Townsend Agency has expanded across the globe with multiple Bosleys (now a rank within the organization) and multiple, multiple Angels. Banks wrote, directed, and starred in this film (as a former Angel who is now a Bosley), and while it isn’t devoid of humor, because the film doesn’t identify as a full-out comedy, the jokes always seem at war with how realistic and serious the film takes itself. There are several pretty cool action set pieces throughout the film, and I can applaud them for thinking outside of the box in trying to bring Charlie into a more modern world, but there’s something that’s disconnected between this film and the series as a whole. In some cases, this film feels like a women’s action film (which I’m here for), retrofitted with Charlie’s Angels skin. And in this retrofitting process, they create some fairly upsetting situations. In this film (*MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD*), the original John Bosley is back (this time played by a jovial Sir Patrick Stewart - they’ve even photoshopped Stewart into stills from Barrymore’s films as Murray’s character, completely erasing Murray from the franchise)...and John Bosley has turned bad! In a film that seems to appear very “rah rah women!” (sorry, Elizabeth Banks, even though you’ve claimed to have not made a feminist film), it seems disingenuous to take the only consistent male character outside of Charlie and make him the bad guy, coloring their entire franchise in a different light. If, perhaps, we had spent a few more films with Stewart as Bosley and we came to this realization slowly, this betrayal would have felt more earned. But in this case, it seemed like more of a dismissal than a celebration of the series it chose to name itself after. Charlie’s Angels doesn’t need dismantling or fixing, like a bomb that needs to be stopped. While the original series was deemed “Jiggle Television,” there’s a way to honor its original intentions while also bringing the series into a new arena. Barrymore’s two Charlie’s Angels films managed to stick the landing. The appeal of the franchise is three beautiful women solving crimes in ridiculous outfits, and the early 2000 films deliver on that promise while still feeling new and distinct. Barrymore has gone on record saying that she would come back for a third installment in her franchise, and the three Angels remain close to this day (Liu and Diaz were her first guests on the first episode of Barrymore’s CBS talk show, and it’s like they’ve never stopped fighting crime since 2003). In a world trying to make space for older women in the entertainment/action industry (thank you, Michelle Yeoh!), I think a new Charlie’s Angels with older Angels is a much more interesting story than a world in which the very fabric of Charlie’s Angels is stripped for parts. So, happy twentieth, Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle. I hope to see an older, wiser, but still silly and kick-ass version of you real soon. A good morning just isn’t the same without ya. Bernadette Gorman-White Managing Editor Bernadette graduated from DePauw University in 2011 with a Film Studies degree she’s not currently using. She constantly consumes television, film, and all things pop culture and will never be full. She doesn’t tweet much, but give her a follow @BeaGorman and see if that changes.

- PODCAST: Hot Takes - Spider-man: Across the Spider-verse

Robby Anderson and Mike Burdge return to that whacky spider-verse for another masterful ride from the folks at Sony: Spider-man: Across the Spider-verse. Listen on....

- A Tribute to Treat (& Dr. Andy Brown, too)

Treat Williams didn’t play the perfect dad, but he was always trying. Actor (Richard) Treat Williams died at the age of 71 on Monday, June 12, 2023, after a motorcycle accident near Dorset, VT. More details about his death can be read here. Treat Williams was known as a real ‘actor’s actor,’ someone who had a great relationship with everyone he met on set, and who continued to stay in touch or provide guidance and mentorship to other actors throughout their careers. An avid skier, he lived in Vermont with his wife Pam Van Sant and their dog Woody on a large farm where more recently, they seemed to be enjoying his less rigorous career. (Williams is also survived by his two adult children Gil and Ellie). Just this past Sunday (June 11, 2023) Williams was posting a photo on Twitter of the view of their farm while sitting on his deck in his pajamas drinking coffee. An in-depth Q&A with Williams in 2021 was published in Vermont Magazine where he talks about his childhood and how he got into acting. (There are some awesome photos of a young Williams portraying Danny Zuko from Grease on Broadway (among many other roles). The published interview is from a longer recorded interview as part of the “Vermont Voices” series. It was tough for me to hear Williams’ voice now that he is gone. It is a warm comforting voice that I have grown familiar with watching him over the years. You can listen to the full interview here: Williams was perhaps most well known during his early career for his starring performance in the 1979 film adaptation of the musical Hair. He talks during his interview about going through 12 auditions before finally being offered the film role. During his final audition, Williams recited a monologue from the stage production while simultaneously stripping down naked throughout. By the time he was finished, the entire crew applauded his performance. He said he didn’t know what else he could offer to prove he was the one for the role and the director offered it to him then and there. Williams had a varied career on the stage, in film, and on television. He received several nominations and some wins for his performances throughout his career, including nominations for two Screen Actors Guild Awards, three Golden Globes, a Primetime Emmy, two Satellite Awards, and an Independent Spirit Award. Williams starred as Dr. Andy Brown on The WB's Everwood from 2002–2006. He was twice nominated for the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance in a Drama Series for his performance. While many may remember him for more comical or action-packed characters, it is as Dr. Brown that I will most fondly remember Treat Williams. Having recently graduated college in 2003, I moved back home and found myself sort of in limbo back in the Hudson Valley. Most of my friends from growing up had moved away (or were trying to). I applied for several jobs, finally landing one in New York City at a Public Relations firm. Without enough money to move, I commuted daily via Metro-North Railroad like many other HV natives. This meant getting up early to drive to the station, often running from my parked car as I heard the train horn blowing upon its approach. I’d pass out on the train ride into Manhattan and often again on the ride home. My mom worked nights as a labor and delivery nurse and my dad often watched sports in the evenings on the big TV in the family room. So after eating dinner and showering, I’d crawl up onto my parents’ king-sized mattress in their bedroom, the only other room that had a television set in our house, to watch something before I got too tired to keep my eyes open. Back then, my comfort came in the form of The WB. That’s right ladies and gentlemen, The WB, not The CW. I had avidly watched Dawson’s Creek throughout my college days but when I returned home after graduation I was left with a void. That void would be filled by a very different show called Everwood, created by the now super-successful Greg Berlanti (Love, Simon, The Flash, Arrow, Riverdale, You, and many more films and shows). In Everwood, a busy and successful brain surgeon from New York City decides to uproot his two children from city life after their mother dies in a car crash. He brings them to the small idyllic (and completely fictional) town of Everwood, Colorado, a place his wife remembered fondly from her youth. Everwood, in particular, that first season, is intensely about grief and guilt. Dr. Andrew “Andy” Brown does not really need to work, he has made more than enough money as a renowned surgeon so he has a sort of idealized idea of becoming a “family doctor” that does not charge his patients. Without spelling it out, it is Andy’s way of atoning, not only for his wife’s death but for his absence as both a husband and a father when she was still alive. Dr. Brown often speaks to his wife in that first season, imagining that she is still there, looking to her for guidance while rearing their children or for comfort when he is lonely. During the course of that first season, most of Everwood goes from being intrigued by the celebrity surgeon to starting to think Dr. Brown has lost his mind, but Williams shows through Andy how grief can consume a person without them even realizing it. Williams as Andy Brown shows a father who has to learn, through trial and a lot of errors, how to be a father to his two children. His old self exclaims how his kids always had the best teachers, the best stuff, but when it came to attention, that always came from their mom. Andy can be a successful world-renowned surgeon and still be a terrible father. All of a sudden he is trying to make lunches and attend school functions with other moms and he doesn't know what he’s doing. He finds he can have temper tantrums just as much as his tween and teenage children. It is when Williams is portraying Andy Brown at his worst and perhaps, his most vulnerable, that I love the character the most. Despite the many terrible arguments Andy has with his teenage son Ephram (Gregory Smith) they also have so many excellent conversations where both parties actually learn from each other. Some of the funniest exchanges happen between father and son on a show that is often described as a family drama. The other side of the coin is Andy’s original adversary, Dr. Harold Abbott (Tom Amandes) who over the course of four seasons becomes one of his closest friends. They have some of the best banter in my opinion. While Everwood never reached as critical acclaim as some of The WB’s other shows, it kickstarted the careers of Chris Pratt (I ❤️ Bright Abbott), Emily VanCamp, and Sarah Drew (along with Gregory Smith). I will always remember when I found out that the show was being canceled. Working for a large PR firm, I was privy to the early knowledge that The WB and UPN networks were about to merge into the new (supposedly improved) CW. Not every show would be picked up by The CW. I held my breath and crossed my fingers but I eventually learned the harsh truth: Everwood was not going to the CW. But you know what show was going to The CW? Seventh Heaven. SEVENTH. HEAVEN. I was livid. Greg Berlanti and crew have said in interviews that they filmed two season finales for the fourth (and now final) season of the show: one in case they were picked up for The CW, and one in case the show was canceled. The show ended but in hindsight, I am glad it did when it did. It allowed the showrunners to end the show on their own terms rather than finishing on a cliffhanger that would never be resolved. In the end, they wrote a conclusion for the series that was both extremely satisfying and still a bit open-ended for the viewers’ imaginations to continue the lives of these beloved characters. I’d be remiss if I didn’t also mention that two weeks ago another beloved Everwood actor John Beasley (who played Irv Harper and the show’s narrator) passed away at the age of 79. Williams paid tribute to his friend and costar on Twitter: Treat Williams had a long and varied acting career - both before and after Everwood - but I find myself going back to that show again and again as a source of comfort every few years. While the younger me identified with Ephram as an angry teen (even during my early twenties), I find I identify more now with the unsure adult Dr. Andy Brown. Rather than a “Father Knows Best” performance, Williams always portrayed Andy as someone who was willing to fail, but more so, who was willing to try. RIP Treat Williams (1951 - 2023). You will be missed. Diana DiMuro Associate Editor Besides watching TV and movies, Diana likes plants, the great outdoors, drawing and reading comics, and just generally rocking out. She has a BA in English Literature and is an art school dropout. You can follow her on Instagram @dldimuro and Twitter @DianaDiMuro

- (Mostly) Devoid of Dialogue

Music as Language in Les Triplettes de Belleville Not many animated films of the past twenty years possess the uniquely strange staying power of Les Triplettes de Belleville. Perhaps this holds true in my memory because as a 15-year-old youth, The Triplets of Belleville came at a time when mainstream film animation was beginning to deviate from the Disney norms of my childhood. Outside of Richard Linklater’s 2001 work, Waking Life, and the inventive work of Studio Ghibli, most popular animation in film in the early 2000s seemed squarely for children. If you wanted something more subversive, you could look to programs of old such as Betty Boop or Felix the Cat, or you could rely on the acid-trip television programming of Rocko’s Modern Life, The Ren & Stimpy Show, Aaahh!!! Real Monsters, and others, but you wouldn’t find anything like that on the big screen. And then came The Triplets of Belleville. Stripped down, and without spoiling too much of the fun, The Triplets of Belleville centers around a grandmother and grandson as they prepare and race in the Tour de France. When the grandson, Champion, is kidnapped by the French mafia during the race, the grandmother, Madam Souza, seeks to rescue him with her companion hound, Bruno, by her side. In her travels, no challenge is too great, but her efforts are eventually matched when she is aided by the titular triplets, whom she meets when arriving in Belleville to save Champion. The film opens with the Triplets of Belleville, a singing variety act, while still in their youth, performing to a throng of fans. The animation instantly hearkens to cartoons of yore, as their attendees are mostly caricatures of married couples, with overbearing, obese women dragging their petite husbands to the theater. This over-exaggeration instantly sets the mood for the spirit of the film, a marriage of old and young animation and storytelling. As the triplets’ show ends, we pan out to see that our two leads, Madam Souza and a young Champion, are watching the show on their television, revealing that this film may be named after the triplets, but the story doesn’t necessarily belong to them. This air of mystery (who are these characters? Will we see the triplets again?) helps to draw you into this fictional version of the Paris countryside and the greater context of the film’s eccentricities. One of the most fun aspects of the film, and a method by which it communicates universality, is that the triplets perform in a city that is a strange amalgamation of Paris, New York, Montreal, and Quebec City. Belleville acts both as a love letter and a criticism of cities that are dedicated to the love of the performing arts. Many of its inhabitants are overtly slovenly, doubling down on the film’s earlier critique between product and consumer in the opening scene. The criticism continues when Madam Souza eventually meets the, now in old age, triplets, and we see that the city of Belleville doesn’t even truly support the artists who bring in the crowds that keep the city alive. The triplets (Rose, Violette, and Blanche) live together in a modest one-bedroom apartment, where they share one bed, and live off a meager diet of frogs that they fish for themselves. But, despite their circumstances, they seem genuinely happy. They come across Madam Souza when she is down on her luck, out of money with no place to stay, and drumming on a broken bicycle wheel. The triplets live for music, and they form a bond in Madam Souza’s drumming, joining her for an impromptu musical collaboration before inviting her to stay with them during her search. It’s through this music that The Triplets of Belleville does most of its communication. There are moments in the film where characters will speak (sometimes in French, sometimes in English), but by and large, the film utilizes sounds, gestures, expressions, and music to illustrate character intents and emotions. The film is mostly devoid of dialogue, and it’s all the better for it. Watching The Triplets of Belleville 19 years ago meant something completely different to me when I was 14, but when watching it again now, it was the music that transported me back to that first viewing. The bits of dialogue are still funny (especially when any of the triplets speak), but the choice to communicate in other ways helped build that sensory memory that can usually only be achieved with a sense of smell. The lack of distinct language also helps to put one at ease while sitting with these characters. Madam Souza is a fish out of water in Belleville, as are we, so we learn as she learns through the language of the film, mostly through body language and the universal language of music. Looking back at this moment in film history through the lens of music, it’s a shame to remember that the 76th Academy Awards had to honor “Into the West” from The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King while The Triplets of Belleville’s “Belleville Rendez-vous” took an L. “Into the West” is an undeniably, powerfully emotional song that The Lord of the Rings trilogy had been building towards for all three films, and it deservedly won that Oscar, but if there was ever a year to hand out a second award, I feel this might have been one of the better opportunities. The Triplets of Belleville also lost out in their only other nomination, Best Animated Feature, to the Pixar powerhouse Finding Nemo. Not to say that The Triplets of Belleville didn’t win awards in other arenas, nor do I wish to intimate that awards are the be all, end all of filmmaking, but it is surprising to look back and realize that for a teenager living in the Midwest in the early 2000s, I was lucky to have known about The Triplets of Belleville at all. Thank goodness for that Academy recognition, no matter how little. Whether this look back inspires you to watch Les Triplettes de Belleville for the first time, or if it’s made you want to take your own stroll down memory lane, I do hope Belleville treats you well. It had been far too long since I had taken the trip myself, and now I can’t imagine waiting as long to pay Rose, Violette, and Blanche another visit. I also can’t imagine ever fully getting “Belleville Rendez-vous” out of my head ever again… Worth it. Bernadette Gorman-White Managing Editor Bernadette graduated from DePauw University in 2011 with a Film Studies degree she’s not currently using. She constantly consumes television, film, and all things pop culture and will never be full. She doesn’t tweet much, but give her a follow @BeaGorman and see if that changes.

- PODCAST: Overdrinkers - The Living Daylights & Licence to Kill

Mike Burdge is joined once again by Reeya Banerjee to talks dat Bond, this time covering the latest news on the new casting, catching up on what they've been watching, and honing in on five very different yet surprisingly connected Bond entries from over the years: You Only Live Twice, Moonraker and The World is Not Enough, but especially the two Timothy Dalton entries from the 80s, The Living Daylights and Licence to Kill. They behave themselves, we promise. Listen on....

- Empathy for the Living & the Dead

A look at The Civil Dead and Jethica An idea most frequently associated with Roger Ebert is the description of films as empathy machines. In 2005 he gave a speech outside the Chicago Theater, when a plaque was being dedicated to him, where he said: “We are all born with a certain package. We are who we are. Where we were born, who we were born as, and how we were raised. We are kind of stuck inside that package, and the purpose of civilization and growth is to be able to reach out and empathize a little bit with other people, and find out what makes them tick, and what they care about. For me, the movies are like a machine that generates empathy.” Now I would push Roger a little on that last line, but only in the sense that it’s not films that make us empathic - we already are unavoidably so by nature - but a film can do an effective job of enlivening our empathy or guiding it in new directions. Exactly how empathy functions is a contentious issue, but there are features of empathy that have been well-established for a long while now. Notably, our empathy is most readily activated by that which resembles ourselves in some way, and this impulse is surprisingly broad in its application. If you’ve ever put a pair of googly eyes on something, then you know firsthand how readily we can anthropomorphize basically anything in the world. It’s this same principle that does a lot of the heavy lifting in most animated films. One wouldn’t think, for example, that you would be able to tell a compelling narrative story about abstractions like our emotions, yet Pixar’s Inside Out was able to sufficiently humanize concepts like Joy, Fear, Anger, Disgust, and Sadness, to tell an enthralling tale. More impressively, that story also was able to say something worthwhile about the young human girl, Riley, that was experiencing those emotions, and by extension, was able to say something about the human experience in general. Almost anything can trigger our empathy, and it reveals something about us when it happens. I say all of this as a preamble to discussing the unexpected role that I see empathy playing in two smaller films from earlier this year: The Civil Dead and Jethica. Both of these films are ghost stories of a kind, though neither is, strictly speaking, a horror film. In both cases, they are stories about people who are haunted by ghosts but are using a literal haunting to say something about being figuratively haunted. They are also both stories that take some pains to get us to sympathize with both the haunter and the haunted. To explain what I think is most interesting about this approach, forgive me for a brief digression into the history of empathy. One of the earliest robust discussions of the mechanism of empathy occurs in Adam Smith’s 1759 book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments. This discussion occurs so early in the historical discourse on empathy that it precedes ‘empathy’ being coined as a term by 150 years. At the time he was writing, Smith and his contemporaries used the term ‘sympathy’ to refer to what we now call empathy. I mention all of this here because the culmination of Smith’s first introduction of what he takes sympathy to be, is his pointing out what he takes to be the furthest extreme of our natural impulse to sympathize: our inclination to sympathize with the dead. What’s so noteworthy about our impulse to sympathize with the dead is that we’re experiencing some kind of fellow feeling with someone we know to no longer be feeling anything at all anymore and that asymmetry highlights how our empathy always says far more about us than it can ever say about whomever we are empathizing with. We can never actually know how someone else really feels, but only how we imagine we would feel in what we take their circumstances to be. Smith says this of our sympathy with the dead: “We sympathize even with the dead, and overlooking what is the real importance of their situation, that awful futurity which awaits them, we are chiefly affected by those circumstances which strike our senses, but can have no influence upon their happiness. It is miserable, we think, to be deprived of the light of the sun; to be shut out from life and conversation; to be laid in the cold grave, a prey to corruption and the reptiles of the earth; to be no more thought of in this world, but to be obliterated in a little time, from the affections, and almost from the memory, of their dearest friends and relations.” For Smith, all of our sympathy for the dead, even our understanding of the dead, only comes to us through a prism of our being alive, and it’s very much that idea that’s at work in these two films I want to discuss. It won’t be possible to fully explore what I want to say about The Civil Dead and Jethica without spoiling those films, particularly their endings. However, since I think not many people have seen them, I’ll begin with a rough sketch of what they’re each about, and let you know where to jump off if they sound like something you would want to check out without being spoiled. The Civil Dead is about a young photographer, Clay (Clay Tatum), who lives in an apartment in LA with his girlfriend. One day, while his girlfriend is away on a trip, Clay goes out to take pictures and runs into someone he used to be friendly with back in his hometown, Whit (Whitmer Thomas). Whit talks Clay into hanging out the rest of that day, and on through the night. Whit finally reveals to a hungover Clay the next morning that Whit has actually been dead this whole time, and is a ghost that only Clay can see and hear. The rest of the film is the two of them navigating that dynamic. Jethica is about two women, Elena (Callie Hernandez) and Jessica (Ashley Denise Robinson), who are each being haunted by the ghosts of men who forced themselves into their lives. Elena is living way out in the middle of nowhere in a trailer in the desert that belongs to her grandmother, trying to figure some things out with her life. One day she runs into an old friend of hers, Jessica, at a gas station. Elena learns that Jessica is driving cross country, seemingly on the run from something, so Elena invites Jessica to come to stay with her at the trailer as long as she needs. Jessica agrees, and once at the trailer, she confides in Elena that the reason she had left home was because of a situation with a stalker that got out of control. A guy named Kevin (Will Madden) had been following her, leaving her unhinged messages, demanding she sees him, and threatening her if she didn’t. Elena hears Jessica out, even listening to some of the messages, and tells Jessica that she’s safe now and can go take a shower and relax. While Jessica is in the shower, though, Kevin shows up outside the trailer, ranting and pacing outside, yelling for Jessica to come out. This is a little bewildering, not least of which because the trailer is truly in the middle of nowhere, nothing but flat desert to the horizon in every direction, and there’s no sign of another car out there. Kevin eventually disappears again, and Jessica brings Elena outside to show her Kevin’s body in the trunk of her car. Jessica tells Elena how Kevin had shown up at her house threatening her, and she had stabbed him in self-defense. She had fled with his body in her car, but his ghost had been haunting her ever since, continuing to stalk her even in death. I’ll pause here because I haven’t yet relayed anything important that isn’t already in the trailers for these two films. If either of them sounds intriguing, please check them out before reading on if the element of surprise is important to you, because each film takes these initial premises in some interesting directions. That warning given, I proceed. What The Civil Dead is interested in, in a loose sense, is what we owe others. The film is told from Clay’s point of view, but there is an interpretation of what happens that would straightforwardly paint him as the villain of this story. When we meet Clay, his girlfriend has just left town, so Clay starts running a scam out of their apartment. Posing as a realtor showing his apartment as available to rent, he holds an open house, collecting application fees from people excited to find such a large apartment available so inexpensively. When we first meet Whit, we learn that he first moved to LA to become an actor, and had reached out to Clay to try to connect with him early on, but Clay kept blowing him off. Even aware of how Clay had been ducking him, Whit is thrilled to now have someone who can see and hear him. At this point, Whit doesn’t know how long he’s been dead, but it’s been a crushingly lonely experience, being invisible, and unable to sleep, or eat, or touch anything. Just stuck existing emptily. Clay and Whit do find a brief camaraderie with one another, in large part because Whit can help Clay with his money problems. Clay wheedles his way into a high-stakes poker game run by a producer he knows, where Whit can tell Clay what cards everyone is holding during the game. At this point, the way the rest of this film could play out is a string of adventures that Clay and his ghost buddy could have, but Clay doesn’t really want that. Clay finds Whit to be too clingy. So, under the guise of arranging for them to be able to spend some quality time together away from Clay’s girlfriend, who still doesn’t know anything about their situation, Clay takes some of his poker winnings to rent a cabin in the woods for him and Whit to go hang out. They go and do even have a fun first night together, but on the second day, Clay lures Whit up into the attic of the cabin, shutting him in up there, knowing that Whit has no way to let himself back out. And the film ends with Whit yelling to Clay for help as Clay packs his car up and drives back home, the cabin slowly receding in the car’s rearview mirror. The way our empathy is manipulated here is impressive. We can step back and look at the way that Clay probably tells this story to himself after the fact and the way this film could have been framed; Clay found himself being haunted, stalked even, by a creepy ghost he never asked for. But, he was ultimately able to outsmart the ghost, trapping it somewhere it couldn’t bother him anymore. What makes the film play out differently than that for us is that we like Whit, feeling bad for what happened to him, both in his life and death; and we kind of think Clay is a douchebag. All of our empathy is with the ghost in this case, because our understanding of what he is going through is all familiar to us as experiences from our own lives: feelings of invisibility, isolation, loneliness, and embarrassment. But even all that said, Clay never consented to being haunted, and doesn’t owe Whit companionship. Clay may be a pretty garbage person otherwise, but it gets really complicated to say what he did was wrong. The way that Jethica plays out is almost the inverse of what happens with Clay and Whit. What we discover that Elena and Jessica have in common is that they are both haunted by men that they killed. In Elena’s case, she was driving down the road, got distracted, and hit a guy walking down the side of the road named Benny. (Andy Faulkner). After he is killed, Benny’s ghost mostly just keeps walking up and down the stretch of highway where he died, and we see Elena sometimes pick him up and talk to him, as a way to make peace with what she did. It’s only towards the end of the film that we learn it wasn’t an accident that Elena hit Benny. She happened to be distracted, and maybe she could have avoided him if she hadn’t been, but he deliberately jumped in front of her car. He was ready to end it all, and she just happened to be the one passing by. The shared theme between Elena and Jessica ends up being women whose lives were derailed by sad and selfish men, but what’s so surprising about where the film decides to go with that is how much empathy it still chooses to have for those two men. Kevin and Benny are undoubtedly the villains of the story, but after Benny absentmindedly reveals to Elena what he did, and Jessica gets Kevin to realize that what he has been doing, in both life and death, has been hurting her, the resolution to the story of the two ghosts is that they stop haunting these women, but also find a friend in one another before finally disappearing. The film doesn’t need to do that, and neither Benny nor Kevin is really owed such grace, but the empathy extended to them is still moving because we can’t help but hope that, even at our worst, such kindness might be extended to us. Neither film does, or really even could, tell us anything definitive about death, but both stories do contextualize something important for us about how we should treat others while we’re alive. How Clay treats Whit isn’t unambiguously wrong, but we still judge him harshly for how little empathy he has for Whit, also seeing it as an extension of the general selfishness with which we already saw him treat others. Clay may not have owed Whit companionship, but it was a choice to be such a dick about it. Conversely, the care that Elena and Jessica showed Kevin and Benny was probably excessive. No one owes kindness to an abuser, but, in general, anyone willing to extend empathy to others tends to receive ours. Such is the esteem with which we hold empathy that we always prefer the one who shows too much to the one that shows too little. And that’s part of why we love films, not because they are empathy machines, but because we are, and a good film reflects that back to us. Damian Masterson Staff Writer Damian is an endothermic vertebrate with a large four-chambered heart residing in Kerhonkson, NY with his wife and two children. His dream Jeopardy categories would be: They Might Be Giants, Berry Gordy’s The Last Dragon, 18th and 19th-Century Ethical Theory, Moral Psychology, Caffeine, Gummy Candies, and Episode-by-Episode podcasts about TV shows that have been off the air for at least 10 years.

- PODCAST: Overdrinkers - The Crow, The Shadow & The Mask

Mike Burdge is joined by Tim Irwin for round two in their Overdrinkers mini-series covering the comic book adaptation surge of the 90s in response to the success of Tim Burton's Batman. In this episode, they talk about three films all released in the year 1994: the angsty The Crow, the ridiculous The Shadow and the superb (and annoying) The Mask. Listen on....

- PODCAST: Cathode Ray Cast - Schmigadoon! S2

On this episode of Cathode Ray Cast, Bernadette is joined by Yarko Dobriansky to talk about season 2 of the AppleTV series, Schmigadoon! They also discuss musicals they've watched in the "Big Apple," how excited they were to see most of the old cast back for another season, and what their favorite new moments were now that they found themselves in Schmicago. Listen on....

- Feeling Lucky, Hank?

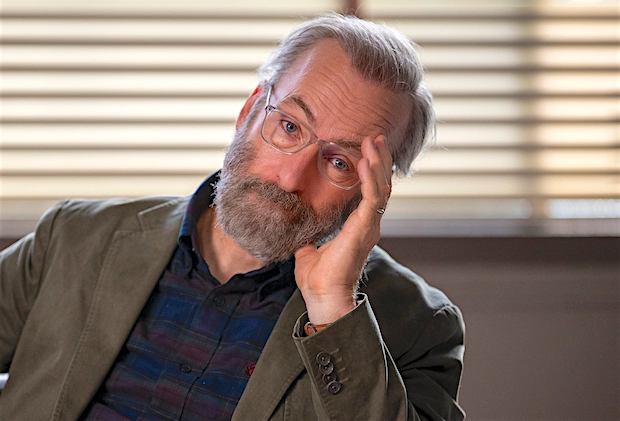

Midlife Crisis? Or the Effects of Lifelong Unresolved Trauma? A review of the new AMC series Lucky Hank CW: this article contains spoilers for the first season of AMC’s Lucky Hank and contains references to suicide. As you may know from my previous listicle about Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul, I love me some Bob Odenkirk and I have been eager to see what he would do next after 14 years of playing Saul Goodman (aka Jimmy McGill), the sleazy lawyer with a secret heart of gold. So I was super excited to see that he was due to star in AMC's new series Lucky Hank, a comedy series based on the 1997 novel Straight Man by Richard Russo, and I happily watched as Odenkirk set off to separate himself from his most famous role. And he did well! Odenkirk plays the titular Hank - William Henry Deveraux, Jr., a tenured professor, and head of the English department at the (fictional) Railton College in (fictional) Railton, PA. Hank is going through a midlife crisis that has ripple effects on his colleagues and his family. He has spent his life trying to be like his father - or his perceived image of his father - a prominent professor of English who abandoned Hank and his mother in pursuit of a prestigious job at Columbia University when Hank was a very young boy. Over the years, the father and son grew increasingly estranged, through a combination of Henry Sr's ambition (and womanizing) and continued disengagement with the family he left behind, and young Hank's increasing resentment at being seemingly forgotten by his father. Lucky Hank's storyline is a deft satire of the (if you pardon the expression) circle-jerk of academia. The petty politics within the Railton English department staff, the ongoing conflict with the school administration about budget cuts, and a clash with a clueless, smug student in Hank’s fiction workshop class reminded me not only of what I witnessed during my own time as a student at a small liberal arts college but also stories my father told me about his time as an English professor at the University of Maryland - a job he fled when my mother, an attorney at a high profile white shoe law firm in Washington DC and the primary breadwinner of the family became pregnant with me. The reason my father gave his family for leaving academia was that babies are expensive AF, my mom was going to be on maternity leave after I was born and then returning to work only part-time until I was old enough for preschool (taking a pause and then a decrease from her generous full-time salary), and professors are woefully underpaid until they get tenure. The official reason, though, was kind of all of the above but mostly because he was just goddamned sick of the petty politics, pressure to publish, and general pretentiousness of being a career academic. He liked teaching, he hated the other stuff, but you can't not do the other stuff and succeed as a professor. So he finished his Ph.D. and walked away, attended business school, and then ended up having a 37-year career in corporate banking. (In our case it ended up being an exceptionally good decision because, by the time my mother was ready to go back to work full time, she was diagnosed with cancer and embarked upon an eight-year battle with the disease. She never did go back to work.) At any rate, the depiction of the environment of an academic workspace in Lucky Hank is very well done and absolutely hilarious. Any hint of Saul Goodman disappears as Odenkirk sinks his teeth into the character of the dour, profoundly depressed Hank (he declares Railton “Mediocrity’s Capital” in the first episode), who begins to spin out when he gets word that his famous father - the one who abandoned him - is retiring from Columbia University. Odenkirk is joined by a wonderfully quirky cast - Diedrich Bader as his best friend, philosophy professor Tony Conigula, Oscar Nunez as Dean Jacob Rose, Kyle MacLachlan as the corrupt college president Dickie Pope, Cedric Yarbrough, Suzanne Cryer, Sara Amini as a few key colleagues in Hank’s department, and the luminous Mireille Enos as Hank's wife Lily, the assistant principal of the local high school. It becomes very clear early on in this show that Lucky Hank is not just about Hank's purported midlife crisis around his career - it's just as much about Lily hitting a crossroads in her career as well. She receives a job offer to be the principal of a prestigious private school in Manhattan - a job that Hank supported her pursuing under the assumption that she would use the offer as leverage to get more money at her job at the high school in Railton. When she realized that the idea of moving to New York and working at a school that has the resources and support she needs to truly pursue her calling as an educator is something she really wants, she tries hard to get Hank to join her in New York, citing it as a new beginning for him - he could start writing again (he only ever published one book and has been working on his second for decades, never able to get much done amidst the demands of being a professor), he could find a different, more fulfilling teaching job, he could get away from his annoying colleagues and the demands of being the head of a department that he hates, he could get away from the mediocrity he espouses in the first episode, and he could forge a path in his life that is independent of his desire to impress his famous college professor father, towards whom he still holds a lot of anger. But Hank is stuck. He seems open to New York at first, then waffles. He says that he doesn't want to abandon his career at Railton (somewhat understandable, as tenured professorships are hard to come by), even though he clearly despises his job. During a dinner party at the Deveraux home with the entire English faculty when the subject of Lily’s job offer comes up, she decides that she’s going to go for it, and the rest of the faculty are thrilled for her. They start peppering Hank with questions about what he will do in New York and who will take over as head of the English department at Railton (and Paul hilariously makes more and more outlandish offers to buy their house - a house he's been coveting since before Hank and Lily moved to town 18 years ago). Hank is not pleased with this development, but Lily has his number and calmly asks him in front of everyone what percentage of unhappy he would have to be to make a change in his life - knowing exactly how unhappy he is because he talks about it at home constantly. At this, Hank absolutely loses his shit, calls his daughter and tells her that her mother is leaving them, returns to the table and screams that he's not leaving Railton and if Lily goes to New York she's going by herself, and has a full-on breakdown, sobbing hysterically, ending the dinner party abruptly and prematurely. This is where I need to pause and say that, much like my irritation with the way Apple TV+ promoted Shrinking as a show about a therapist who goes rogue with his patients as a way of dealing with grief when really it was a show about complicated grief and how healing it is to have a chosen family to help you through it, I am massively irritated that AMC promoted Lucky Hank as a show about a college professor having a midlife crisis. Hank is not merely having a midlife crisis. Hank is dealing with massive childhood trauma due to his father's abandonment - a situation that is casually tossed off in one line by Lily while she's trying to mediate a fight between her daughter and her son-in-law and never mentioned again. The downplaying of this trauma on the show is absolutely absurd. Because not only did Hank's father leave him and his mother, but on the day he was leaving, a young Hank, in despair, attempted suicide. Hank thankfully did not succeed, but when his father found him on the ground with a noose around his neck, he didn't acknowledge what had happened, instead walking away and calling out for Hank's mother to deal with it. And Hank's mother's solution to the problem was a hug and a promise to pretend the suicide attempt never happened. Hank then spends his entire life hating his father, missing his father, trying to become his father, and struggling with the unresolved grief he has over his father's abandonment. Lily is well aware of the circumstances of Hank’s childhood, and his suicide attempt, and yet the series keeps trying to portray Hank’s behavior as the quirky offbeat mannerisms of a man who’s just having a midlife crisis. The tone of the humor around Hank’s genuine despair is, quite frankly, inappropriate given the severity of what the character has suffered through. A compounding effect on Hank’s existing trauma is that his father has relocated to Railton after retirement inexplicably to live with his ex-wife, Hank's mother, who it turns out has agreed to take care of Henry Sr as he is struggling with age-onset dementia. Henry Sr's mental condition prevents Hank from properly confronting his dad about the abandonment, as his father doesn't even remember what happened, basically blocking Hank from attaining anything even remotely close to closure about a seismic event in his childhood that he has struggled with for his whole life. Is it any wonder that he wigs out when his wife takes a job in New York? Even though she wants him to come with her, to him it feels like a repeat of the scenario where his father abandoned him to take a job in New York. "Why are you trying so hard to leave me?" he wails at the aforementioned dinner party. When Lily says that her decision to take the job has nothing to do with her feelings towards him (she wants him to come with her!) he can't hear it. All he can see is someone who he loves trying to leave him behind. As a fellow sufferer of childhood trauma with severe abandonment issues (that'll happen when you watch your mom fight cancer for 8 years and then die when you are still a child), this scene, in particular, resonated strongly with me. This is hard for me to admit, but I have said and done similar things in the past in my relationship under similar circumstances. It's not logical. It's not rational. It's not based on fact. But the emotions are overwhelming and losing control - and being unable to shift perspective and actually listen to the words being said to me, words that are trying to reinforce that I am loved and there is no intention to abandon me - is all too easy when your entire body shifts into fight or flight at any presumed threat to the safety of the status quo. The big problem with Hank is that his unaddressed trauma impacts everyone around him. He insults three years' of Tony’s work after a failed presentation at a conference by making a not-well-thought-out joke about how conferences are dumb, resulting in his best friend, deeply hurt, telling him that he doesn't understand how year after year Hank becomes more cynical, more withdrawn, and more depressed without doing something about it. Decision paralysis is another key hallmark of unresolved trauma, and Hank's decision paralysis leads him to keep stonewalling Dean Rose when asked to provide a list of three professors in his department to cut for budget reasons as decreed by the nefarious Dickie Pope, leaving the employees in Hank’s care on edge and in limbo. Hank screws over Meg, one of his post-doc students, by refusing to give her any classes to teach even though he could have, because he is passively trying to force her to leave Railton and not get stuck there like him - but he isn't honest with her about why he does it, causing a permanent rift in that mentor-mentee relationship. And while he's so focused on pushing Meg to leave Railton, why won't he himself leave? Why won't he go to New York with his wife? The season culminates in Hank finding a way to expose Dickie Pope's corruption and questionable reasons for the budget cuts, thus saving the jobs of his colleagues and the other departments who were subject to layoffs. After trying to share the good news of his success in saving his department with his father, hoping to receive some kudos from the former esteemed academic, he learns that his father was forced to retire from Columbia not for his dementia, but because he had falsified a memoir piece that was about to be published claiming he had participated in the 1965 Civil Rights March on Selma and in the fact-checking process the falsehood was discovered. When Hank asks why his father would do something so reckless, Henry Sr claims that it’s not that big of a deal (and his mother infuriatingly agrees), saying he did it because that’s the job of a career academic: you do what you have to do to keep getting published, you have to keep publishing to remain relevant, to keep getting invitations to conferences, give talks, appear on panels, be “famous” - even if the fame is only in the rarefied world of higher education. By the time you get to the level of prominence that Henry Sr reached, that dubious fame becomes part of your sense of self, and losing it is destabilizing. This rather shocking and pathetic reveal from his father seems to be the wake-up call Hank needs to get away from a career path he hates. He submits his resignation to Dean Rose and drives to New York, finally feeling free of his burdens, to be with his wife. But we end on a point of ambiguity - Lily doesn't seem all that happy to have him there in her new Brooklyn apartment. When she first arrived in New York for her new job, she indirectly admitted to one of her grad school friends that she's considering asking Hank for a divorce - that in the marriage she feels she has grown. He's remained where he was when they first met, and she can't keep taking care of his needs at the expense of her own. She doesn't say this to Hank when he turns up on her doorstep, triumphant with his success at saving his colleagues’ jobs, sticking it to Dickie Pope, walking away from the circle-jerk of academia and the looming specter of his father's abandonment in his psyche, and consciously deciding to change his life by coming to New York and fully supporting Lily's career the way she did for him for so long. While he excitedly whoops with joy in the bathroom, she sits down on her new bed in the new space that she’s set up exactly the way she wanted quietly, with an uncomfortable look on her face. And in the meantime, Dean Rose, upon reading Hank's resignation letter, immediately puts it in the shredder. Hank may think he's released himself from the shackles of Railton College and has found a new start, but it seems that those around him may not feel the same way. Lucky Hank is a smartly written, fun romp in the pretentious world of academia, and it's also a thoughtful exploration of the complexities of a marriage between two people who love each other dearly but may have grown apart. (And Bob Odenkirk boxes a goose!) There's great stuff here, and I'm excited to see how this all continues to shake out next season. But until AMC - and the showrunners - accept that the show is not about a professor having a midlife crisis, but about a deeply traumatized man with maladaptive coping mechanisms he developed in place of treating his trauma who may be permanently destroying his marriage, leaving him languishing in a career that exacerbates his depression, the real heft of the emotional stakes at play in Hank's story won't ever be fully realized. I liked the first season of Lucky Hank a great deal. It’s smart and witty, the dialogue is sharp, the season’s structure is well-plotted, and the characters are very well-developed - even the more minor characters who make up the English faculty Hank oversees at Railton. I hope that the show can do a bit of a course correction for season 2 so that we fully acknowledge the harm that Hank has inadvertently wrought (and those around him have enabled) on himself due to his unresolved trauma and see if he's capable of healing and true change, or if he is going to remain stuck and repeat the cycle of family abandonment trauma that has so truly damaged the course of his life. You can catch the entire first season of Lucky Hank on Prime Video with an AMC+ subscription. Go check it out. Bob Odenkirk’s work as Hank is exceptional (despite the show’s flaws), so much so that you may even forget that Saul Goodman exists… Reeya Banerjee Staff Writer Reeya is a musician and writer based in New York's Capital District. Her debut album, “The Way Up,” was released on January 27, 2022. She can frequently be seen in her car on the NYS Thruway cursing traffic on her way to the Hudson Valley for band rehearsals or to Brooklyn for recording sessions. In her other life, she works as a staff accountant for a management company that oversees veterinary practices nationwide, enjoys watching Law & Order SVU returns while eating gummy bears, and has a film degree from Vassar College that she does not use.

- PODCAST: Freakin' Out with Flanagan - The Haunting of Hill House

On this episode, Diana DiMuro and Mike Burdge are haunted by the charm of guest Tim Irwin, as they discuss Flanagan's breakout limited series: The Haunting of Hill House. There are a lot of ghost jokes. Listen on....

- Never Say Neverland