Search Results

876 items found for ""

- PODCAST: Hot Takes - Godzilla Minus One

Mike Burdge and Tim Irwin chat about that dang big boi, Godzilla, who has once again taken the world by storm with their passive aggressive city smashing and glowy roar lasers. The movie is absolutely stunning. Listen on....

- PODCAST: Overdrinkers - The Matador

Mike is joined by returning holiday guest, Yarko Dobriansky, to chat about a new Christmas classic they've been revisiting the past few years: 2005's hitman-dark-comedy, The Matador. Along the way, they talk about the careers of the cast, Brosnan's recent ventures, what makes something ACTUALLY a Christmas movie, and somehow, Lost. Listen on....

- PODCAST: Overdrinkers - The Muppet Christmas Carol

Mike Burdge and Diana DiMuro kick-off the week of Christmas by visiting an ol' classic in their household: The Muppet Christmas Carol! Topics of discussion include Michael Caine's INSANE performance, the Muppet line-up as a whole, the different types of Muppet movies they grew up with, and of course, chickens. Listen on, and Happy Holidays!

- (MEMBERS) Ep 62: The Collette Stuff - Nightmare Alley

Bernadette and Mike return the magical world of Toni Collette's filmography, catching up on her work from the past couple years. Films and projects discussed include Nightmare Alley, Pieces of Her and The Staircase. Listen over on our Patreon Page.

- (MEMBERS) Ep 53: Overdrinkers - Darkman, Dick Tracy & The Rocketeer

Mike Burdge and Tim Irwin start off a new Overdrinkers mini-series covering the comic book adaptations of the 90s that were directly inspired by the tone and success of Batman (1989). First up, it’s Sam Rami’s notoriously awesome, Darkman (1990), Warren Beatty’s batshit bananas Dick Tracy (1990) and Joe Johnston’s inarguably fun, The Rocketeer (1991). Along the way, they discuss the changes in comic book and superhero adaptation fare, as well as the successes and failures of the genre over the past 30+ years. Listen on…. Overdrinkers Cocktail: The Rocke-Who? 2 oz Floral Gin 1/2 oz Vodka 1/2 oz Luxardo Maraschino 1/4 oz Orange Curaçao 3/4 oz Lemon Juice Combine all ingredients with ice and shake well. Strain into rocks or coup glass, serve neat or on the rocks.

- Goodbye, Mr. Yunioshi

The Case for Remaking Breakfast at Tiffany’s For a while now, I’ve had an ongoing text thread with friends of mine where we play the daily internet movie games, like Framed and Movie Grid. Framed in particular ends up being a fun game to play with others because, even when none of us can guess what the day’s movie is, it’s rarely ever anything so obscure that it doesn’t spark some kind of conversation for the group. An especially interesting one to me from a little while ago was Blake Edwards’ 1961 film, Breakfast at Tiffany’s. It’s a film with a peculiar kind of stature. It features one of the more iconic performances ever put on film in Audrey Hepburn’s turn as Holly Golightly, while also being a film that hardly ever seems to get screened or discussed anymore because it also includes one of the most egregious instances of yellow face you’ll ever see, with Mickey Rooney’s performance as Mr. Yunioshi. Though the film’s seemingly growing obscurity may be deserved, it is a shame because of how much I think the worthwhile parts of the film and its story still have to offer audiences. One of the more enduring images of the 60’s film is a 31-year-old Hepburn from this film: her hair up, wearing the definitive little black dress, bejeweled, and wielding her foot-long cigarette holder. I saw more than a few people dressed as her just this past Halloween. And yet, I don’t know what fraction of people who know that image could tell you anything about the film's plot. This iconic image is much better known as representing Audrey Hepburn than it is for her character, Holly Golightly. And yet, it’s hard to recommend to such people that they go back and watch this film, because Rooney’s performance isn’t just racist through a modern lens, it ought to have been seen as out of bounds even for the time. The performance also isn’t something that pops up just once that you can fast forward through but rather is a “running gag” that shows up repeatedly throughout the film. I’ve talked to people on both sides of the issue. Some folks have never made it past Rooney’s first appearance, and some folks have been watching the film for so long that they have gotten used to living with Rooney’s scenes as the cost of getting to enjoy the rest of one of their favorite films. I can see how Breakfast at Tiffany’s could be someone’s favorite film, too. Beyond Hepburn’s performance, she has spectacular chemistry with her co-star, George Peppard, as Paul Varjak, the aspiring novelist who has just moved in upstairs from Holly and reminds her of her brother Fred. Blake Edwards' direction sparkles at times, particularly in the party scenes in Holly’s apartment and during Holly and Paul’s day of new adventures in the city. Henry Mancini’s score is also an endless pleasure, deservedly winning Oscars for Best Score and Best Original Song, “Moon River.” All that said, because of Rooney’s performance, it’s still a film I can never really feel comfortable recommending; So, I’ve concluded that it’s time to remake Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Remakes are a dicey proposition, especially with films that are regarded as classics. It’s generally going to be ill-advised to try to remake some beloved favorite with an enduring legacy, like Singing in the Rain or It’s a Wonderful Life. But, as we recently saw with Spielberg and Kushner’s update of West Side Story, even an accepted classic can be reinvigorated in the right hands. I’m especially keen on the idea of a remake of Breakfast at Tiffany’s because I’ve always been more fond of Truman Capote’s original novella than the film it was based on anyway, and the story is one that, if told faithfully, may have even more salience now than when the film was made. The film and the novel manage to largely depict the same events while also telling fundamentally different stories. The film, with its happy ending, is something of a romantic comedy. With this framing, it makes sense that it was one of the touchstones when Nathan Rabin was first outlining the idea of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. Set in the mid-20th century, a young writer, notably unnamed in the novella, moves into a building in New York City, where he comes into contact with his vivacious and charismatic upstairs neighbor, Holly Golightly. The nature of Holly’s life is ambiguous in both the film and novella, but she supports herself on the gifts and money she gets from socializing with men, and from money she is paid to make weekly visits to a former crime boss in Sing Sing. While much of Holly’s life is shaped by men pursuing her, she is the one who interjects herself into her neighbor’s life one night when she comes down the fire escape to get away from a bothersome man she had brought home to her apartment that night. She’s somewhat taken with her neighbor because of how much he reminds her of her beloved brother Fred, and she even takes to calling him ‘Fred’ for most of the rest of the story. The handling of this connection between Holly’s neighbor and her brother marks what might be the biggest point of departure between the film and the novella. In both, it’s this connection that allows Holly to be more vulnerable with her neighbor than she is with others, particularly other men. But, while in the film, this connection is the seed of the romantic tension between them, in the novella, this is what allows Holly to give her neighbor access to her life in a way she wouldn’t for all the men that are sexually interested in her. In the novella, she calls her neighbor by her brother's name and singles him out as what she hopes is a safe harbor, something she is greatly in need of as she’s trying to make a way for herself in the world. The other most significant change between the novella and the film is never made explicit, but there is a very apparent difference in Holly’s age. Audrey Hepburn was 31 when she played Holly Golightly, while the character is only 19 in the novella. That difference has always underlined for me the degree to which men’s relationship towards the young Holly of the novella was more overtly predatory. We learn the same backstory for Holly in both the film and the novella. Her real name is Lulamae Barnes. She and her brother Fred were orphans who had run away from cruel foster parents. They end up surviving in part because when they are caught stealing from the farm of a local veterinarian, named Doc Golightly, he takes pity on them and brings them into his home. At the time, Lulamae was only 13. She would be 14 when Doc married her, making her the mother to his 4 children. Later, when talking about this with Fred, after Doc finds her in New York and tries to talk her into coming back home, she doesn’t look back with any regret about her time as a child bride but recognizes it wasn’t a real marriage. She did love Doc, and in the novella even sleeps with him again before being sent back to Texas. But she ran away because it wasn’t the life she wanted. This pattern would repeat in LA where she would be taken in by another older man, O.J. Berman, a talent agent who wanted to turn her into a movie star. It’s in running away from that life that she finds herself in NY. Holly Golightly who is only 19 wears these experiences differently than the 31-year-old Audrey Hepburn. Hepburn’s Holly is chic, sophisticated, and self-assured. This Holly is the one that fits the mold of Rabin’s original idea of the manic pixie dream girl. She confidently lets herself in through the window of her sensitive writer neighbor, she assuredly presents him with a different worldview than the one he’s known, and she coaxes him into new adventurous experiences, before ultimately settling down with him for a happily ever after. In the novella, not only do they not wind up together, but much of the point of the story is that, despite her numerous messy shortcomings, Holly remains fiercely, maybe pathologically, independent, despite the many efforts of the men in her life to put her into particular boxes or social cages. The very framing device of the novella is that Holly’s story is explicitly told through the male gaze. The character that Mickey Rooney plays in the film is actually important to the novella, because Holly’s upstairs neighbor, I.Y. Yunioshi, is a photographer who regularly travels internationally on assignment, and it’s a photograph that he takes that sparks the narrator to tell the story. Yunioshi, while traveling in Africa, is shown a small carved idol of a woman’s head that looks so much like his former neighbor, Miss Golightly, that he takes a picture of it, and sends it back to a barkeep in NY that shows it to our narrator. So, at this point, everything in the story we’re about to read has already happened, and Holly is long gone. In the novella, this isn’t the love story the film makes it out to be, but rather a story about a barkeep and unnamed writer hung up on the literal graven image of a woman they loved, who left them behind on her way to bigger and better things. For all the strengths of the original film, it’s themes and ideas like these that I would love to see a new film explore. Damian Masterson Staff Writer Damian is an endothermic vertebrate with a large four-chambered heart residing in Kerhonkson, NY with his wife and two children. His dream Jeopardy categories would be: They Might Be Giants, Berry Gordy’s The Last Dragon, 18th and 19th-Century Ethical Theory, Moral Psychology, Caffeine, Gummy Candies, and Episode-by-Episode podcasts about TV shows that have been off the air for at least 10 years.

- PODCAST: Overdrinkers - Judge Dredd, The Phantom & Spawn

Mike Burdge and Tim Irwin cover another trio of 90s comic adaptations, this time taking a peek at Judge Dredd, The Phantom and Spawn. Topics of conversation include recording at Tim's new house, the destruction of Billy Zane's career, the heights we allowed John Leguizamo to go to, and of course Tim's Gun Corner™. Listen on....

- PODCAST: Cathode Ray Cast - And Just Like That S2

Covering the latest season of And Just Like That, Bernadette is joined by Reeya Banerjee to discuss how season 2 improved upon season 1, while knowing that the show still has a long way to go to getting a consistently good story. They chat about their favorite storylines (Miranda and Steve coming to an understanding, Charlotte and Harry being ridiculous) and their least favorite (Aidan's total copout of an exit, terrible children) all the while begging for more depth from side quest characters (Seema, LTW, and Nya). Listen on....

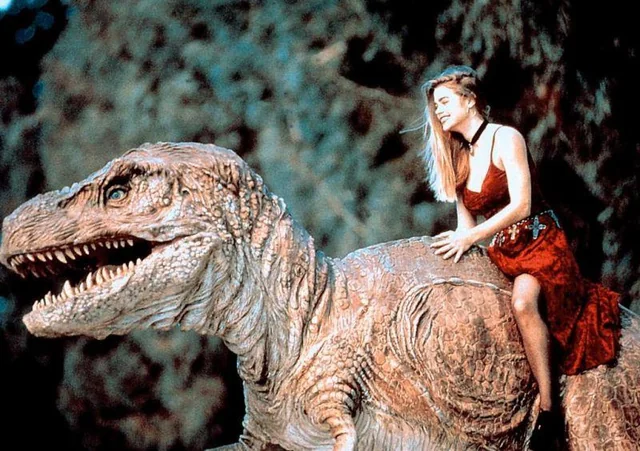

- I ❤️ Genre: Tammy and the T-Rex

I ❤️ Genre is a new series written by Jeremy Kolodziejski providing retrospectives and analyses of frequently unknown gems of the strange and unforgettable genre cinema that he loves sharing with others. On a fateful day in 1993, British screenwriter Stewart Raffill, known for The Ice Pirates as well as Paul Rudd’s favorite movie Mac & Me, was approached by a man who owned several movie theaters in South America. He informed Raffill that he had access to a giant animatronic Tyrannosaurus Rex. He asked if Raffill could direct a film prominently featuring the T-Rex. I think anyone could relate to this opportunity. Who wouldn’t want to make a movie featuring a giant robot T-Rex? Especially in the early 90s when a certain film about Dinosaurs broke box office records. (I’m of course referring to the Roger Corman-produced Carnosaur, unless there’s another dinosaur film I’m forgetting about.) However, there was a catch: Raffill only had access to this animatronic beast until the end of that month. He had to write, produce, and direct an entire 90-minute feature in two weeks. He remained resourceful, filming in his hometown, using a local crew, and he managed to produce an entire film within those two weeks. He did not even let a forest fire (which was occurring during the film) stop him, and he incorporated its orange haze into the background of a few shots of the film. That film became Tammy and the T-Rex. What did Raffill come up with in such a short time period? Well, it’s a film that contains, in a word, multitudes. Not only does it contain dinosaur attacks, but also lion attacks, grave robbing, brain swapping, evil horny nazi scientists, dinosaurs making phone calls, and men settling their differences with a testicular throwdown. It even features a title called the wrong name (reading as Tanny and the Teenage T-Rex for some inexplicable reason.) The movie is a wild ride from beginning to end. Now, Tammy and the T-Rex could have very easily become an unmitigated and forgotten disaster not worth discussing or even mentioning nearly 30 years after its release, and for a long time, that was the case (I will get into that later). However, it’s not the film’s insane set pieces or its bizarre sense of humor that makes Tammy and The T-Rex so memorable and rewatchable, although that helps. While Raffill was casting the film, two young actors who had yet to star in any film miraculously walked through the door and (in my opinion) saved the film. These two young actors were Paul Walker and Denise Richards. You can tell while watching the film that even without the benefit of hindsight, these two actors were meant to be movie stars. Their charisma and watchability are so potent you can’t help but be engrossed by such a deranged premise. Richards has to act alongside a robotic T-Rex that can barely move, and yet, she remains so charming that she sells their relationship enough to get you weirdly invested in its outcome. When Tammy and the T-Rex was initially filmed, it was intended to be an R-rated horror comedy, filled with gory special effects of people getting dismembered and eaten, as well as a whole extended brain surgery sequence. These special effects certainly are not up to the quality of the likes of Tom Savini or Stan Winston, but they are gross and cheesy enough to be effective for the tone the movie is going for. However, right before its release, the film’s producers got cold feet, cut out all the blood and gore, and tried to repurpose the film as a family comedy. It did not get a theatrical release, going straight to VHS, making that version of the film the only known version for nearly 25 years, where it remained in mostly obscure corners of VHS collectors and hardcore dinosaur fans. In 2019, the miracle workers at the restoration and distribution company Vinegar Syndrome discovered the original uncut version of Tammy and the T-Rex, restored it in 4K resolution, and released it for all to see. Now Raffill’s original film is fully available in all its gorey glory. If you are looking for something to watch with a bizarre sense of humor and an almost randomly occurring story with two future breakout movie stars, you can’t go wrong with Tammy and the T-Rex. It’s even available in its entirety to watch through the video game High on Life, idly playing in the player’s living room. Not the most ideal way to watch a film, but it is there! Jeremy Kolodziejski Jeremy is a long-time supporter of and contributor to the Story Screen Fam, as well as the entire Hudson Valley Film community, as a writer, filmmaker, film worker, and general film fan. You can find him sifting through the most obscure corners of horror, martial arts, comedy, noir, and crime drama cinema, always on the hunt to discover something new, strange, and exciting.

- Bohemian Rhapsody: 5 Years On

A Celebration of a Force of Nature It's wild to me that Bohemian Rhapsody - the musical biopic about the life of Queen frontman Freddie Mercury - has already hit its 5th anniversary. Released on November 2, 2018, in the United States, the film chronicles the story of Queen’s formation in 1970 through to their famous 1985 Live Aid performance at Wembley Stadium. It's wild to me that it's been five years since its release because I remember the anticipation I felt about it like it was yesterday. In fact, I wrote about it here, for Story Screen, five years ago in my article about South Asian representation in media. I remember my elation when it was announced that Rami Malek was cast as Mercury, especially given that the industry buzz for so long was that Sacha Baron Cohen was in the top running for the role. Casting Cohen would have been infuriating, regardless of his superficial physical resemblance to Mercury, because it is offensive - period, end of story - to have a white actor play a character of Indian origin. Malek's casting was not a 100% perfect choice, but given that Mercury was born to a British Parsi family it was pretty damn close; Parsis are an ethnoreligious group within India that adhere to the Zoroastrian religion, and are descended from Persians who migrated to Medieval India during and after the Arab conquest of the Persian Empire. Rami Malek is the child of Middle Eastern immigrants. Freddie Mercury (born Farrokh Bulsara) was the child of Indian immigrants who descended from the Middle East. Sacha Baron Cohen is a white man. Brownface is not okay. I'll stop pounding on this drum now; I think you get my point. The film is not without its flaws; there are some timeline discrepancies in the film regarding when certain Queen songs and albums were released and which tours they were on and when - the kind of stuff that would be very annoying to music history pedants like me. The film does seem to very strongly suggest that Mercury was gay when by all accounts he was bisexual. I'm not a fan of the film’s bi-erasure and the entire story of how Queen ended up participating in Live Aid seems to have been invented in cold cloth to ratchet up character drama. In the film, Mercury comes back to his band after working on a middling solo career, hat in hand, apologizing for being an egomaniac and implores them to agree to participate in the benefit concert, and they really make him beg for it, whereas in real life, by all accounts, the band had already agreed to reunite to do the show without all of this behind-the-scenes melodrama and weren’t having petty squabbles about it. I wonder about the need to invent character tension for tensions' sake, I wonder why these timeline liberties were taken, and I wonder about the bi-erasure, mostly because Queen’s guitarist Brian May, and drummer Roger Taylor, were heavily involved in the film's production. They were there, they knew and loved Freddie Mercury, and it seems puzzling to me that they would be okay with that level of dramatic liberty taken with a story that is as much about their lives as it is about Mercury's. Despite these quibbles, what makes this film such a joy to watch are its performances. Malek quite simply disappears into the role of Freddie; he captures his speaking patterns, mannerisms, and incomparable physicality with such ease. His performance is astonishing, and the Oscar he received for it was well-deserved. But while Malek carries the film, it's worth noting that the producers did an amazing job in casting the rest of Queen - Gwilym Lee looks and sounds exactly like May, from the wacky perm to his politely bemused-yet-affectionate attitude towards Freddie's flamboyance. Ben Hardy captures Taylor's bad-boy attitude and intense drumming style with great aplomb. Joe Mazzello nails bassist John Deacon's quintessential pragmatism, unfussiness, and impeccable precision (all qualities in any good bass player - as a bass player, I know of which I speak!). The four actors together have incredible chemistry and they really feel like a band - a band of exceptional and visionary musicians, a band of brothers, a true family who loves each other, not despite each others' quirks and foibles, but because of them. It's heartwarming to see how kind and gentle and supportive May, Deacon, and Taylor were when Mercury informs them that he has been diagnosed with AIDS because we know that that's how they were in real life. They were a band that was loudly groundbreaking when it came to musical inventiveness and exploration, and they were also quietly groundbreaking in that three straight rock-n-roll lads from London were so accepting of their friend and frontman's sexuality and his struggles to fully accept himself. This film is a celebration of those unique qualities that made Queen the musical and pop cultural force of nature that it was. The end of the film is a near-recreation of their famous Live Aid set, and I remember sitting in the theater watching it back in 2018, feeling choked up by the nostalgia of it all - which is absurd, because I was only three months old when Live Aid happened and till that day in the theater, I had only seen Queen's Live Aid set on YouTube. But that's the thing about Freddie Mercury - his voice, that magnificent, four-octave range - was and is a voice that captured the hearts of people all over the world, and echoes on and on, even three decades after his death at the age of 45. Far too young. AIDS was a guaranteed death sentence back when Mercury was diagnosed with it - and it was considered a guaranteed death sentence for most of my childhood as well. It's wild to me that we now live in a world where that is no longer the case - where it is now treated as a chronic condition that can be managed with medication and lived with indefinitely. If Freddie Mercury had survived long enough to benefit from the significant advances in medical research and the treatment of AIDS, I am certain that we would still be watching Queen do world tours along with their contemporaries like the Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen, and Paul McCartney. I've seen the Stones, Bruce, and Paul live in concert many times. But what I wouldn't give, as a musician of Indian origin myself, for an opportunity to see Freddie Mercury live, to hear that glorious voice and feel that unstoppable charisma. It sadly won't ever happen, but there's always YouTube - and there's always Rami Malek, channeling him so wonderfully in this film. It's not 100% perfect, but it's pretty damn close. Reeya Banerjee Staff Writer Reeya is a musician and writer based in New York's Capital District. Her debut album, “The Way Up,” was released on January 27, 2022. She can frequently be seen in her car on the NYS Thruway cursing traffic on her way to the Hudson Valley for band rehearsals or to Brooklyn for recording sessions. In her other life, she works as a staff accountant for a management company that oversees veterinary practices nationwide, enjoys watching Law & Order SVU returns while eating gummy bears, and has a film degree from Vassar College that she does not use.

- Good Luck in Reality

The Barbenheimer experience during troubled times It’s a sociocultural fluke of world-historic proportions, and I admit that I want it to answer for more things about this supremely fucked-up moment on our planet than it possibly could. The unintentionally simultaneous, epiphanic release of both Barbie and Oppenheimer quickly morphed into a Barbenheimer meme well before the films’ concurrent theatrical debut on July 21, courtesy of Sean Longmore’s brilliant, deeply faked Barbenheimer poster. This gave way not long afterward to no less curious international irruptions of the Barbenheimer experience, including an authentically historic dustup among Wikipedia editors over whether there should actually be a standalone Barbenheimer page defining the phenomenon (they ultimately decided to keep the page up five days before the films’ release) and a crossover into reality different from those found in Barbie’s plot occurred at an Oppenheimer screening in India which accidentally projected that film along with subtitles for Barbie. The buzz was irresistible, leading to a combined domestic box office take of $246 million for the two films’ first weekend. Predictably, Barbie took a commanding lead with $162 million but Oppenheimer came in decisively in second place, bolstered by a sizable portion of their overall audience proudly taking in both films as the unlikeliest double-feature in recent memory, and subsequently posting about it on social media. As day follows night, this led to a blizzard of commentary about Barbenheimer, ranging from predictable business news panegyrics praising their initial box office take as one of the biggest domestic opening weekends ever, to Richard Lawson’s even-handed itemizing the “lessons” Hollywood may learn, or not (like I say: even-handed), for Vanity Fair. Even Francis Ford Coppola was moved t o opine about Barbenheimer in a story posted to his Instagram profile, where the renowned director admitted that, while he has “yet to see [either Barbie or Oppenheimer],” he insisted that “the fact that people are filling big theaters to see them and that they are neither sequels nor prequels, no number attached to them, meaning they are true one-offs, is a victory for cinema.” That Coppola was compelled to remark on the films without actually having watched them speaks volumes to something compelling about both films and their composite Barbenheimer identity, but also to a pronounced sense of cultural exhaustion this early into a new century, when the twin successes of a movie about a popular doll and a respectful, big-budgeted historical drama can feel radical and potentially transformative. The sober docudrama and the multi-generational corporate brand turned on its blonde, pink head; an implicit plea for feet-of-clay integrity in a corrupt world and, all of its self-aware attempts to subvert itself while fully meta-acknowledging those attempts notwithstanding, arguably the single greatest instance of product placement in American history — the Barbenheimer binary goes well beyond Lawson’s claim that we are only dealing with a “big girl movie and a big boy movie,” much less with films which owe nothing to franchises or superheroes. While the meme is already well in the rearview mirror, both films continue to dominate the box office, having already raked in $2 billion collectively worldwide and climbing. Socioculturally, we’re just starting to unpack these films and their collective impact; something about their collisions with fantasy and reality, if articulated in diametrically opposite ways, has caught on in this disconcerted moment. Barbie is, vastly and unsurprisingly, the more popular and multi-generationally relevant of the two, both as a film and a statement on behalf of, among other things, female empowerment — it’s fair to ask if Oppenheimer would have anything like its current impact without it. There is an undeniably shared intelligence at work behind both films, something that extends to their dispositions toward their subject matters, beginning with genuine respect. But Greta Gerwig’s direction of Barbie comes leavened with considerable, distancing irony, a trace of her origins and the long path Gerwig has traveled since she co-wrote and starred in films by herself, Joe Swanberg and other members of the so-called “mumblecore” movement in the earlier part of this century, which proudly stood in opposition to rote American cinematic conventions. Over a decade later, Gerwig is writing and directing prestigious adaptations like Little Women and now Barbie, bringing her own microindie-honed sensibility and discursive non-linearity to bear in often surprising, brilliantly funny ways. But these qualities cannot help but occasionally boomerang their way back to their savvy creator, given the inescapably commodified nature of her subject. Similarly, Oppenheimer director Christopher Nolan has his own indie origins and showy non-linear inclinations but shifted into major mainstream success much earlier in his career with Memento and the Dark Knight trilogy/franchise. Nolan’s respect for his subject here is also more conventional, less ironic, one that sits comfortably with his other films like The Prestige and Dunkirk in their fidelity to the past and world-historical “big themes.” But trouble sets in early; consider Barbie’s opening sequence. Ostensibly a gender-reversed homage to the opening sequence of 2001: A Space Odyssey (a sequence, let’s recall, titled “The Dawn of Man”) where Barbie, embodied for the first time in the film by the brilliant Margot Robbie, serves as The Pink Monolith, one that compels the assembled girls from another era into doll smashing, an unnerving inversion whose implications it’s hard to imagine a writer-director as intelligent as Gerwig somehow missing. In 2001, it’s implied that the Monolith somehow conveys to the pre-human hominids how to use bones to attack rival tribes, leading to the brutally celebrational smashing of other bones at the end of the sequence; human agency, even the first use of tools, is steeped in violence, death and literally inhuman intervention. By creating an homage to this scene, exactly what has Gerwig “reversed” for Barbie’s first literally inhuman intervention? It’s clearly meant as a joke and I am in danger of over-literalizing Gerwig’s intent here, but there’s no escaping the fact that dolls — the subject(s) of the film — are effectively weaponized during Barbie’s opening credits, well before our heroine even gets around to mentioning her death obsession. Strangely enough, Barbie ultimately proves to be more death-obsessed than Oppenheimer, the docudrama about the father of the atomic bomb and its eventual guilty conscience with self-professed “blood on (his) hands”, J. Robert Oppenheimer. Its opening sequence certainly reveals the scope of its ambitions, putting Cillian Murphy’s underplayed Oppenheimer in a direct encounter with the problematic figurehead of the highest modernism, Picasso, as Oppenheimer contemplates his 1937 canvas “Woman Sitting with Crossed Arms.” Quite conversely, there’s eventually something ploddingly dutiful about Nolan’s film, an echo of his protagonist’s dedication to beating the Nazis to nuclear warfare, as horrific as crossing that finish line might be, as something he must do and which he subsequently tries to prevent from happening again once the Cold War quickly begins, striving for dignity in a world where politics prove to be less about morality than maneuvering. One positive aspect of that dutifulness is Oppenheimer’s overall faithfulness to the actual historical record regarding its subject: Oppenheimer’s education, leftist political inclinations and attendant associations, his heading up of the Manhattan Project and the enemies he gains before and after WWII, culminating in a hearing where he loses his security clearance, in every sense but legally a trial, one which serves as a through line for the film as it hops back and forth across its protagonist’s own timeline. It’s a well-traveled trope for Nolan by now — employing a narrative elasticity as certain episodes unfold from beginning to end — and his formal control over multiple plotlines developing in forward, parallel motion is as distinctive here as in his past work. This approach is shot through with recollections, as fragments from significant points in the storyline return like barely repressed memories, and Oppenheimer makes time for many of them; I’ve taken to calling these characteristic Nolan tics his “Bruce, why do we fall?” shots. The tone is one of efficient, reserved morality, though Nolan does suggest early on some of the thrill of Oppenheimer’s training and the times, notably in Europe, when they take place. When Murphy’s no less reserved Oppenheimer is asked by Kenneth Branagh’s Franz Boaz if he can “hear the music” of theoretical physics, you can be sure we both hear Ludwig Göransson’s bombastic score and see whorls of presumed electrons cycle in dazzling ovals in Oppenheimer’s dreams. These early scenes, slightly nutty, over-literalized in their own right, and dispersed through Nolan’s asymmetrical editing style, suggest a version of A Beautiful Mind directed by Terence Malick. But the rush from this mix of corny literalizing and Cubist engagement is fleeting in Oppenheimer, and the film quickly gets down to the generally banal narrative task of detailing the creation of the atom bomb and Oppenheimer’s comparatively modest professional downfall, standing apart (and, occasionally, above) it all. In a glaringly ahistorical gesture, however, Nolan’s sense of duty leads him to strive for an otherwise commendable inclusiveness which, coming from the first half of the 20th century, is considerably more aspirational than factual. For all of Nolan’s noble efforts to highlight a black or Latinx character here, or a female scientist there, no Black scientists lived at the Los Alamos, NM facility, the primary site of the Manhattan Project’s atomic testing, prior to 1947. And while there were over 600 hundred female employees, more than half of whom were scientists, at Los Alamos during the creation of an atomic bomb, they get at best token recognition in Oppenheimer. It’s a lamentable trend in Nolan’s film work to date: female characters are often denied the agency and self-determination of his male protagonists. Though, in the case of Oppenheimer, this is a no-less lamentable instance of historical accuracy where Oppenheimer’s real life was concerned: patriarchy was the unquestioned way of the world, not nearly as easily dismissed, ignored and ultimately triumphed over as it proves to be in Barbie. Instead, we get Florence Pugh’s Jean Tatlock and Emily Blunt’s Kitty Oppenheimer on the sidelines, his former lover and subsequent wife respectively, both generally afflicted in specific ways that reduce their role in the overall narrative, making them serve less as actual characters than as two more burdens for the film’s noble albeit “womanizing” hero to bear. Their afflictions may also be historically accurate, but Nolan has made his own choices about how to portray these women’s contributions to Oppenheimer’s life; in an echo of Nolan’s Inception, for example, Tatlock ultimately did commit suicide, something irregularly recalled throughout the film in the Nolan manner. But having her (or, rather, Pugh) appear naked in a perverse fantasy during Oppenheimer’s security clearance hearing registers as wrongheaded and disturbingly misogynistic; the scene jumps out in the middle of the movie with a garish tawdriness. In a similar vein, their first sexual encounter also plants Oppenheimer’s legendary quotation from the Bhagavad Gita during the first atomic test ("I am become Death, destroyer of worlds"), one of many Oppenhemier’s docudramatic version of running gags, a little death giving a foretaste of the mass execution to come. Nolan shows little more taste when Murphy imagines stepping into the charred remains of a Japanese victim of his creations — incidentally, this is the only instance in the film which acknowledges actual victims of Oppenheimer’s work, and only in a fantasy. This little death and ashy shoe are about as much of a death obsession as one gets from Oppenheimer. Separately, Blunt is usually drunk and hectoring; even when she’s right about, for example, the duplicity of Robert Downey Jr.’s Atomic Energy Commission chairman Lewis Strauss, it’s only in passing and with drink in hand. Careful with broad historical strokes, it’s often in these revealing details that the film falters, and this includes a certain degree of anachronism. Did someone really play bongos at Los Alamos, over a decade before they would become a punchline for the emerging Beat movement? It’s hard to imagine a decade before that Pugh’s Tatlock suggesting “You just need to get laid” to Oppenheimer, an expression unlikely to be used even by 30’s Communist fellow-travelers. To be clear, Oppenheimer is undeniably smart Hollywood entertainment whose high regard for its subject and nuanced view of its legacy make the film consistently watchable. But it’s a slow boil, not a nuclear blast — compression is the name of Oppenheimer’s game, leading to a middle-register, undercooked tone throughout, one that renders sedate outdoor scenes and the first successful atomic test nearly equal in dynamic range. This is further reinforced by some not particularly adroit expository attempts at introducing biographical particulars into the dialogue; references to “those dark stars you’re working on” or a family which, like so much else in its protagonist’s life, proves more discussed than actually seen in the film. One of those running gags is a reiteration of its hero’s observation: “Theory can only take you so far.” For Nolan, his serious dedication to his subject doesn’t take you much farther in practice. Barbie doesn’t come freighted with the same biographical challenges, pitching Barbieland as a gender- and race-conscious utopia, but trying to engage the doll’s problematic legacy on multiple, self-aware levels creates a few issues of its own. Gerwig certainly doesn’t help herself by creating twelve literal straw men in the form of Barbie’s all-white male Mattel corporate board, where Mattel has had a comparatively good record for hiring female CEOs and having diverse board membership. Ahistorical or no, it may have been worth it just for incurring Bill Maher’s tweeted wrath over this small plot departure from reality in a children’s film. To be sure, the urge to take this summer movie about dolls seriously begins with its filmmaker. Gerwig is happy to leverage the doll’s problematic relationship to feminism in entertaining but sometimes ambivalent ways. When Ariana Greenblatt’s Sasha, daughter of America Ferrara’s fictional Mattel secretary Gloria, chastises Robbie’s “Stereotypical Barbie” as a “fascist,” it’s a double-edged condemnation: both of the ease some have for invoking fascism and to the Malibu-bourgeois Barbie’s undeniable white, multi-normative legacy. Moments like these are funny, but also somewhat self-canceling. The porous separation between reality and fantasy is deftly achieved in Barbie, where a feminist paradise becomes troubled by Gloria’s “real-world” attempts at reconciliation with the course of her adult life and finding solace in her own manifestations of a differently “Weird Barbie.” That reconciliation ultimately takes precedence, as Greenblatt gets pushed to the margins while somehow objecting less, coming around and getting with the program, surely fulfilling a wish of a few mothers I know. Gloria’s now-famous monologue about the impossible, contradictory demands placed on women introduces a complexity of thought and emotional affect rarely matched in Barbie, to say nothing of other American big-budgeted films this century. For good and ill, it sets a standard the film can’t always rise to — to take one example, if only patriarchy was as easy to ignore as Sasha’s goofy father for the entirety of the film. There’s no denying the liberating energy of this knowing, female-centric blockbuster almost incidentally aimed at a younger audience. Being able to engage the problematic nature of her subject using the best, most crowd-pleasing Hollywood conventions, up to and including the musical number, is no small feat. Gerwig told the New York Times “Things can be both/and. I’m doing the thing and subverting the thing.” Gerwig’s product placements macro- and micro-, all the way to the final appearance of the Mattel logo as a device to censor Issa Rae’s expletive, will ultimately obtain more to Mattel’s stockholders than to any thing-subversion, no matter how amusing they are. In the end, however, Gerwig squares the circle with Rhea Perlman’s Ruth Handler, Mattel’s founder, someone with her own problematic personal history. Taking Robbie’s hands towards the end in a delicately multicolored fantasy-space, the scene gives way to actual amateur footage of real-life mothers and daughters from across the decades, fading in and out of each other like streams of unrepressed memories. Resolutely unironic reality wins the day and grounds the proceedings in instances of unaffected mother-daughter affection, a dialectical victory of cinéma vérité over problematized fantasies (including fantasies of reality), all helping this singularly hyper-ironic work cruise its way to billions in box office. Although all parties insist there will be no sequels, it will be interesting to see how much of Gerwig’s own newly-minted brand transfers over to her proposed Chronicles of Narnia adaptations. And for all of Oppenheimer’s reserved gravity and self-importance, in its layered, adroit self-reflexivity, Barbie oddly proves to be the more serious film of the two. And yet, in another unexpected synthesis, both of these auteurs’ agendas ultimately prove less compelling than their films’ performances — the casts for both films are extraordinary. Robbie, and Ryan Gosling’s “Beach Ken,” are pitch-perfect in their initial guilelessness transforming into troubled self-awareness, where Ferrara grounds the film in her character’s attenuated anguish. Robbie’s sister-Barbies do tend to blur together, with the huge exception of the gifted Kate McKinnon: if there really were going to be any franchise spinoffs from this film, we could only be so lucky if they began with “Weird Barbie.” Michael Cera, to the surprise of no one, once again excels in the Michael Cera part. Nolan extends his track record of exemplary work with well-cast performers, as Pugh and Blunt bring considerably more depth and irascible vitality to their characters than the script alone provides them. Downey — at first courtly and brittle, but slowly revealing a malevolence marinated in humiliation — delivers what is for me his finest performance. And Oppenheimer’s back bench is unusually deep: I didn’t initially recognize bespectacled Josh Hartnett in his square, all-American affability as Oppenheimer colleague Ernest Lawrence, a smiling Dad from a 1940’s Boy’s Life cartoon come to life. Equally unrecognizable (and far from lookalikes for their characters) are Tom Conti’s reflective Albert Einstein and Gary Oldman’s prickly Harry S. Truman, the latter of whom did in fact say that he "never wanted to see that son of a bitch in this office again," although most likely not, as the film portrays it, within earshot of Oppenheimer as he was leaving his one face-to-face meeting with Truman at the White House after WWII. Benny Safdie’s range continues to impress, his choleric, arrogant Edward Teller a world away from his portrayal of Robert Pattinson’s mentally-challenged, locked-up brother in Good Time, a film Safdie co-directed. But by far my favorite performance is Jason Clarke’s calm, ruthlessly all-business Roger Robb, the AEC special counsel at Oppenheimer's security hearing who makes mincemeat of Oppenheimer’s self-serving obfuscations and outright lies about his radical past and his associates. This teeming canvas of charismatic actors working in harmony with Nolan’s vision is the best recommendation I can give for seeing Oppenheimer. Popular culture inexorably draws upon and thus reflects, in general unintentionally, the times within which it is created and it’s usually only in retrospect that these manifestations are appreciated as the almost natural expressions of those times, seen in historical relief. Is the Barbenheimer experience somehow tied to a global desire to transcend our current problematic sociopolitics, with both knowingness and solemnity? Or, is it simply a fun, distracting goof to take in these quite different films as a meme-worthy fusion? Most likely, it’s both and more, with resonances that will reveal themselves in time. In any of these or other cases, our troubled times have found some solace, reflection and vindication with Barbie and Oppenheimer, or maybe just five hours of desperately needed smart entertainment in a world seeming to spin out of control. As Barbie crosses into it for the first time, Dua Lipa’s “Mermaid Barbie” calls out: “Good luck in reality!” She might as well be wishing it for all of us. James Keepnews James is a musician, writer, and multimedia artist. James’ writing has appeared in Chronogram, Pacific Sun Magazine, New Haven Advocate, and other publications. His previous pieces for Story Screen include: A Dangerous Method, "The Gods Are Coming Back!", “’Have a Nice Apocalypse’ —The Resolute Irresolution of Southland Tales,” and “Archives and Morals: Jean-Luc Godard and the Boundless Provocations of The Image Book.”

- PODCAST: Story Screen Reports - Strike News and Miramax Wins Big

Want to help striking actors? Donate to the Entertainment Community Fund Story Screen Reports is our team REACTING to the top 5 film, television and entertainment news stories of the month. Join us as we dissect and comb through everything from upcoming releases to studio drama. On this episode, Mike Burdge joins Robby to chat about more updates on the Writers and Actors Strikes, a Halloween cinematic universe on the horizon, Ridley Scott NOT being a grump for once, and A24 isn't gonna be just for honk-shoo nerdz anymore! You can find those stories, and the sourced articles, linked below. Eat the rich, and Happy Halloween, spooky fam! 1. Hollywood Writers Strike is Over as Union Wins Major Concessions From Studios Written by Austen Goslin and Oli Welsh at Polygon 2. Actors Strike Sees No End in Sight After Studio Negotiations Go Awry Written by Andrew Dalton for USA Today 3. Halloween - Miramax Slashes Into The TV Rights to the Franchise Written by John Squires at Bloody Disgusting 4. Ridley Scott Watched the New ‘Alien’ Movie and Said “It was Fucking Great,” Says Director Fede Alvarez: I was ‘Terrified’ Waiting For His Reaction Written by Zach Sharf at Variety 5. Report: A24 to Expand, Produce More Commercial Films Written by Raphael Helfand at The Fader Listen on....